100x Efficiency Improvement For Solar Energy Device

By Ron Grunsby, editor

Scientists at the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) have taken another step closer to their goal of effectively converting both the sun’s light and heat into electricity, making a solar energy device 100 times more efficient than its previous version. The device, based on the photon-enhanced thermionic emission (PETE) process, uses a semiconductor chip to produce electricity by utilizing the full spectrum of sunlight, including wavelengths that generate heat.

“A conventional photovoltaic cell is extremely efficient at harvesting the sun’s energy in a narrow band of frequencies,” said Jared Schwede, a Stanford graduate student who performed many of the PETE experiments. “The sun comes in a broad range [of frequencies], and all of this additional energy is not harvested as well in a photovoltaic cell and instead goes to waste as heat. … PETE puts this additional energy to use. In addition to the photovoltaic effect that will drive a conventional solar cell, this additional heat energy is used to boost the output voltage of a PETE device.”

The PETE process was initially demonstrated in 2010 by a team led by Nicholas Melosh, associate professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford and a researcher with SIMES, and SIMES colleague Zhi-Xun Shen, the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory's advisor for science and technology. SIMES is a joint institute of SLAC and Stanford University.

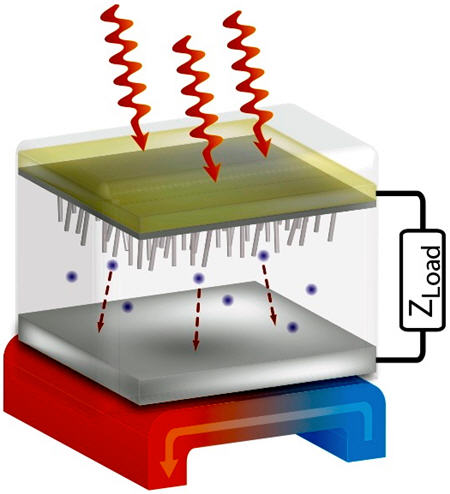

In a recent report in Nature Communications, the scientists discussed how they improved the device’s efficiency from a few hundredths of a percent to almost 2 percent. The improved chip features a sandwich of two semiconductor layers – one to absorb sunlight and create free electrons, and the other to emit the electrons from the device to be collected as an electrical current. The electrons’ passage from the chip is helped by a cesium oxide coating on the second semiconductor layer. The researchers aim to achieve at least another 10-fold efficiency gain by developing new coatings or surface treatments to preserve the atomic arrangement of the second layer's surface at high temperatures.

Concentrated sunlight (red arrows at the top) heats up the device's semiconductor cathode (beige and grey upper plate) to more than 400°C. Photoexcited hot electrons (blue dots) stream out of the cathode's nanotextured underside down to the anode (white/gray surface), where they are collected as direct electrical current. Additional solar and device heat is collected below the anode (arrow shows the cool-to-hot, blue-to-red flow) to run electricity-generating steam turbines or Stirling engines. (Credit: Nick Melosh)

PETE devices produce electricity using thermionic emission, which gains efficiency at high temperatures. This makes them suitable for utility-scale concentrating solar power plants, such as multi-megawatt power tower and parabolic trough projects in California's Mojave Desert. At these plants, mirrors are used to direct sunlight into extremely bright, blazingly hot regions that boil water into steam, which spins an electrical generator. Adding PETE devices to these plants may raise their electrical output by 50 percent.

"When placed where the sunlight is focused, our PETE chips produce electricity directly; and the hotter it is, the more electricity it will make," Melosh said.

The promise of this huge benefit will inspire the researchers to tackle their next major challenge – figuring out how to make the device withstand the 500° temperature swings at solar power plants from day to night.

What do you think about this technology? How do you see it evolving? Please share your thoughts below.