World's First Room Temperature Maser Using Diamond Developed

The world’s first continuous room-temperature solid-state maser has been developed by UCL and Imperial College London scientists.

The breakthrough, made using a diamond held in a ring of sapphire, opens up the possibility for masers (microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) being used in a wide variety of applications such as medical imaging and airport security scanning.

Masers are the older, microwave version of lasers and have traditionally been used in deep space communication and radio astronomy. They were invented in 1954 but their use has been limited because, until now, they must be cooled to temperatures close to absolute zero (-273°C) to function.

The study led by researchers at the London Centre for Nanotechnology and published today in Nature, reports for the first time a maser that can work continuously at room temperature.

Professor Chris Kay (London Centre for Nanotechnology at UCL) said: “This is a huge development and really opens up what we can use masers for in the future. I think they could play a pivotal role in improving communications on earth and in space, increasing the sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging and even contribute to the realisation of quantum computers.”

In 2012, the team demonstrated that a maser could operate at room temperature using the organic molecule pentacene. However, it only produced short bursts of maser radiation that lasted less than one thousandth of a second. Had the maser operated continuously, the crystal would likely have melted.

To address this, a synthetic diamond grown in a nitrogen-rich atmosphere by Element Six was used to create a new maser that operates continuously.

Carbon atoms were ‘knocked out’ from the diamond using a high energy electron beam, creating spaces known as ‘vacancies’. The diamond was then heated, which allowed nitrogen atoms and carbon vacancies to pair up, forming a type of defect known as a nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centre.

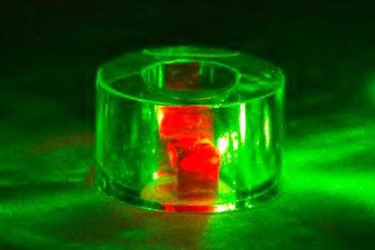

When placed inside a ring of sapphire to concentrate the microwave energy, and illuminated by green laser light, the researchers found that the maser worked at room temperature and importantly, continuously.

Dr Jonathan Breeze, from Imperial’s Department of Materials, who led the study, said: “This breakthrough paves the way for the widespread adoption of masers and opens the door for a wide array of applications that we are keen to explore. Hopefully, the maser will now enjoy as much success as the laser.”

Co-author Professor Neil Alford, also from Imperial’s Department of Materials, said: “This technology has a way to go, but I can see it being used where sensitive detection of microwave radiation is essential”.

This work was funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and supported by the Henry Royce Institute.

Source: University College London