Thermal Management In Dense Photonic Integration

By John Oncea, Editor

As photonic integrated circuits pack more components into smaller chips, power density and thermal effects create fundamental performance limits through thermo-optic resonance shifts, crosstalk, and stability challenges that scale nonlinearly with integration density.

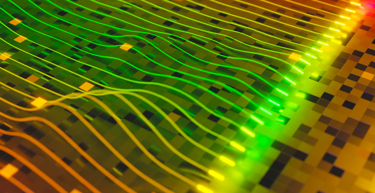

Photonic integrated circuits promise to revolutionize computing by transmitting data at light speed while consuming far less energy than their electronic counterparts. The vision is compelling: optical signals racing through silicon waveguides, free from the resistance and heat that plague copper interconnects. Yet as engineers push toward higher integration densities, packing thousands of components onto chips mere millimeters across, they confront an uncomfortable reality. The very devices meant to replace heat-generating electronics are creating thermal management challenges that threaten to limit the technology’s potential.

The problem is particularly acute because photonic devices, unlike their electronic cousins, are extraordinarily sensitive to temperature. While a transistor might tolerate several degrees of thermal variation with minimal performance degradation, a silicon photonic ring resonator can shift its operating wavelength by tens of picometers for every degree Celsius change. In wavelength-sensitive applications, inevitable temperature fluctuations cause undesirable performance variations, requiring either active stabilization or on-chip compensation for practical deployment, according to Optica. This sensitivity, combined with increasing power densities as components shrink and multiply, creates what some researchers describe as a major bottleneck to photonic integration.

The Thermo-Optic Effect: Silicon’s Double-Edged Sword

At the heart of the thermal challenge lies silicon’s thermo-optic coefficient – the rate at which its refractive index changes with temperature. Silicon’s coefficient is approximately 1.8×10⁻⁴ per Kelvin near 1550 nm, roughly an order of magnitude larger than that of silicon dioxide cladding. This property makes silicon ideal for thermo-optic tuning, where controlled heating adjusts device characteristics. But it also means that uncontrolled temperature variations wreak havoc on circuit performance.

The impact manifests most dramatically in resonant devices. Microring resonators demonstrate tight temperature limits (±0.1K) for high-Q filtering applications, with chip-level heat loads of a few watts concentrated in areas of a few square millimeters, leading to local heat fluxes exceeding 100 W/cm². According to Springer Nature, these specifications seem almost contradictory: generate substantial heat in a tiny volume while maintaining temperature stability to within a tenth of a degree. Yet this is precisely what dense photonic integration demands.

The extreme temperature sensitivity of silicon photonic devices, combined with high integration density, makes thermal management crucial to guarantee correct functionality, according to MDPI. In optical phased arrays, where hundreds or thousands of phase-sensitive components operate side-by-side, temperature gradients cause different refractive indices across the chip. The result? Beam steering errors, wavelength drift, and system failure.

Consider a densely-packed wavelength division multiplexing system with multiple ring resonator filters. Each filter must maintain its resonance wavelength with picometer precision to correctly route optical signals. A temperature increase of just 5°C shifts the resonance by roughly 440 picometers – enough to completely misalign the filter with its intended channel. Now multiply this sensitivity across dozens of components, each potentially heating its neighbors, and the scale of the challenge becomes clear.

Resonance Drift: When Precision Becomes Impossible

The temperature dependence of silicon photonics creates a moving target for system designers. Studies show that if a constant thermo-optic coefficient is assumed in a representative design case, predictions can underestimate temperature-induced channel wavelength shifts by up to 10% across the operating temperature range. The coefficient itself varies with both temperature and wavelength, adding another layer of complexity to device modeling.

For microring modulators used in high-speed communications, resonance drift presents a continuous calibration challenge. Thermal drift measurements show resonance shifts of approximately 87.5 pm/°C for air-clad silicon resonators, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Over a typical data center temperature range of 25-80°C, this translates to wavelength shifts exceeding 4.8 nanometers – far larger than the free spectral range of many compact ring designs.

The problem compounds in systems requiring multiple wavelength channels. In dense WDM systems with channel spacings under 1 nanometer, even minor thermal drift can cause adjacent channels to interfere. According to Colorado State University, optical signals suffer from both optical loss and intra- and inter-channel crosstalk accumulating through different stages in the circuit. The accumulated crosstalk degrades signal quality and limits the achievable bit error rate, effectively capping system capacity.

Thermal Crosstalk: The Integration Density Killer

If resonance drift affects individual components, thermal crosstalk attacks the entire system architecture. The phenomenon is straightforward yet pernicious: heat generated by one component raises the temperature of neighboring devices, causing unwanted shifts in their operating points. When a thermal shifter dissipates power, heat can reach waveguides different from the target one, inducing undesired phase shifts, according to Wiley Online Library.

Crosstalk severity depends heavily on component spacing and thermal isolation. Research demonstrates that in programmable photonic meshes, thermal crosstalk can cause degradation of up to 85% in neural network classification accuracy when not properly accounted for. For systems with multiple thermal phase shifters operating simultaneously, crosstalk creates a complex interdependence where adjusting one element affects all others, according to arXiv.

Integration density of silicon photonic integrated circuits is strongly constrained by thermal crosstalk due to the wide use of the thermo-optic effect, according to AIP Publishing. In some reported designs, spacing on the order of hundreds of micrometers up to approximately 1 millimeter is used to keep crosstalk manageable, absent additional isolation structures – a distance that severely limits integration density and chip functionality.

The crosstalk mechanism is not merely resistive thermal conduction but involves complex heat spreading through the substrate and cladding layers. According to IEEE, traditional resistive coupling models do not suffice for photonic integrated circuits; new coupling methods must account for dynamic thermal behavior. This complexity makes predicting and compensating for crosstalk in large-scale circuits computationally intensive and often unreliable.

In practical terms, thermal crosstalk limits how many active elements can be placed in a given area. In some laser array designs, spacing on the order of tens of micrometers (∼50 µm) is used to maintain sub-0.1 K temperature uniformity between emitters, according to ResearchGate. For circuits with hundreds of components, these spacing requirements quickly consume chip real estate and undermine integration benefits.

Scaling Laws: When More Becomes Impossible

The relationship between integration density and thermal management is decidedly nonlinear. As component counts increase, thermal issues don’t merely scale proportionally – they compound. Each new heat source contributes to the ambient chip temperature while simultaneously creating new crosstalk pathways to existing components.

Power density emerges as a fundamental limit. Traditional metal-based thermo-optic phase shifters typically require tens of milliwatts per π phase shift, though modern optimized designs using advanced geometries and materials have demonstrated power consumption as low as 2-3 mW per π shift, according to NCBI. Without aggressive cooling, it becomes difficult to scale to hundreds or thousands of thermo-optic shifters if each consumes tens of milliwatts; practical implementations typically budget only a limited fraction of chip power to thermal tuning.

The thermal resistance network becomes increasingly complex as circuits grow. Simple analytical models fail to capture the coupled thermal behavior of densely integrated systems. Finite element simulations require hours-scale computation to model dense wavelength-division multiplexing ring filters, and even then provide only static thermal profiles rather than dynamic responses.

Consider the scaling challenge from a systems perspective. A 100-element programmable photonic circuit might manage thermal effects through careful layout and modest active cooling. Scaling to 1000 elements increases not just the heat load tenfold but creates 10 times more crosstalk interactions – roughly 100 times more thermal management complexity. At 10,000 elements, the challenge becomes formidable with current techniques, though some groups have successfully demonstrated photonic meshes into the 10²–10³ element range with careful thermal design and control.

Thermal Design Strategies: Fighting Back

Engineers have developed multiple strategies to combat thermal issues, ranging from passive compensation to active control systems. Each approach involves distinct trade-offs between performance, power consumption, and complexity.

Active thermal management remains the most common solution. Integrated resistive heaters allow precise temperature control of individual components, compensating for both ambient temperature variations and crosstalk effects. According to Nature, electronic controllers can automatically set working points and lock photonic functionality in real-time, though at the cost of continuous power consumption. A single thermal shifter operating at steady-state may consume several milliwatts to several tens of milliwatts just to maintain temperature, depending on design.

For applications requiring sub-ambient temperatures or exceptional stability, thermoelectric coolers provide precise control. Multi-stage TECs can maintain laser arrays at 15-25°C even in 40°C ambient conditions. However, TECs add substantial cost, complexity, and system-level power consumption – often exceeding the power budget of the photonic chip itself. These are generally system-level rather than on-chip TECs.

Structural thermal isolation offers a passive approach. In one reported design, according to MDPI, air isolation trenches etched into the silicon substrate reduced required safe distances by up to 80%, from approximately 1400 micrometers to around 280 micrometers. These trenches create thermal barriers that block heat conduction between circuit regions. Advanced designs using closed heat shield structures can manipulate thermal flux to bypass temperature-sensitive components, though implementing such structures without disrupting optical and electrical interconnects remains challenging.

Material engineering provides another avenue. Utilizing glass substrates with high-density through-glass vias for thermal paths allows thermoelectric coolers to control PIC temperature while glass’s thermal insulation suppresses crosstalk from adjacent electronic integrated circuits, according to MDPI. Diamond heat spreaders offer exceptional thermal conductivity, though simulations indicated modest thermal-performance gains in specific wire-bonded assembly configurations studied, Optica adds.

Athermal Device Designs: Compensation Through Cleverness

Perhaps the most elegant solution to thermal sensitivity is to eliminate it through athermal design. These approaches use material or structural compensation to create temperature-insensitive devices that require no active power for thermal stabilization.

Material-based athermal designs exploit opposing thermo-optic coefficients. Silicon’s positive thermo-optic effect can be compensated by negative effects from polymer claddings, creating composite waveguide structures where temperature-induced index changes cancel out, according to MIT Libraries. The design involves carefully engineering the waveguide geometry to control how much of the optical mode overlaps with each material. Co-polymer claddings offer improved performance compared to homo-polymers, with enhanced thermo-optic coefficients and better mechanical stability.

Demonstrations have achieved remarkable results. Polymer claddings on silicon ring resonators reduced thermal drift from 87.5 pm/°C to approximately 40 pm/°C – better than 50% compensation. With optimization, athermal designs targeting 0 pm/K wavelength shift have demonstrated prototype performance of 0.5 pm/K, enabling stable operation without active temperature control.

Structural compensation offers an alternative approach. Mach-Zehnder interferometers using asymmetric arm designs achieve temperature-dependent wavelength shifts below 2 pm/K – more than four times better than conventional designs, according to IEEE. The principle relies on deliberately mismatching the thermal behavior of the two interferometer arms such that their phase shifts compensate rather than add.

Despite these successes, athermal designs face limitations. Integration in electronic-photonic architectures requires multi-layer stacking capability and hermetic sealing to protect sensitive materials. Post-fabrication trimming using photosensitive layers can fine-tune athermal performance, but adds process complexity. Most significantly, athermal approaches work well for specific device types but do not fully solve system-level thermal management where multiple component types with different temperature sensitivities must coexist.

Power Dissipation Limits: Optical Vs. Electrical Pumping

The distinction between optically-pumped and electrically-driven photonic systems reveals fundamental trade-offs in power efficiency and thermal management. Optically-pumped systems use an external laser to provide gain, while electrically-driven devices generate light through current injection.

Optically-pumped silicon Raman lasers and parametric oscillators can achieve ultra-low power consumption because they avoid the inefficiency of electrical-to-optical conversion on chip. According to arXiv, demonstrations of optically-pumped photonic crystal lasers under specific pulsed modulation conditions measured energy consumption around 13 fJ/bit – orders of magnitude better than many electrically-pumped alternatives. The catch? These systems still require an off-chip pump laser, whose power consumption rarely factors into reported efficiency metrics, and these extremely low values apply to particular experimental regimes rather than general operation.

Electrically-driven systems confront harsh realities of quantum efficiency and carrier dynamics. Early electrically-pumped photonic crystal nanocavity lasers exhibited threshold power dissipation around 260 microWatts in specific device implementations. The difference compared to optically-pumped versions stems from non-radiative recombination, carrier leakage, and resistive losses in current injection structures – all of which generate heat.

For integrated photonic circuits requiring light sources, the thermal implications are substantial. Some authors argue that the thermal and yield challenges make off-chip or co-packaged lasers preferable in many current systems, though the silicon photonics community is actively pursuing on-chip and co-packaged laser integration. Yet external lasers require fiber coupling, which introduces optical loss, alignment challenges, and system-level complexity.

Electrically-pumped devices also face efficiency limits in the driving electronics. Transimpedance amplifiers in many short-reach photonic links contribute a significant fraction of the receiver power budget, according to AIP Publishing. The power consumption characteristics of these electrical circuits scale with both speed and voltage requirements, creating cumulative power dissipation challenges in dense systems.

Recent advances in heterogeneous integration offer hope. Electrically-driven soliton microcombs using III-V laser diodes coupled to high-Q silicon nitride microresonators demonstrate that careful co-design can achieve both electrical operation and reasonable efficiency, according to NCBI. The key lies in using gain materials where they’re needed while leveraging silicon’s excellent passive optical properties.

Ultimately, power dissipation limits integration density through thermal constraints. Heat dissipation is a limiting factor to packing density in membrane photonic components, with thermal resistances typically in the range of 100-500 K/W depending on cladding materials. A chip producing 10 watts of heat requires sophisticated packaging and cooling solutions that increase cost and complexity. Co-packaged optics systems target integration densities exceeding 400 Gb/s per square centimeter while managing thermal loads, but achieving these densities demands unprecedented attention to thermal design from device through package level, according to NCBI.

Looking Forward: The Path To Higher Integration

The future of dense photonic integration hinges on overcoming thermal limitations through innovation at multiple levels. Material advances, particularly phase-change materials and emerging electro-optic materials with reduced thermo-optic sensitivity, promise devices with inherently better thermal behavior. According to Nature, wide-bandgap phase-change materials achieving low loss and high cyclability could enable non-volatile programmable circuits that eliminate continuous power consumption.

Three-dimensional integration architectures offer geometric solutions. Vertical stacking of photonic and electronic layers with intelligent thermal management allows heat sources to be physically separated from temperature-sensitive optical components. 3D photonic wire bonding enables high-density interconnection without planar crosstalk limitations, though thermal coupling between layers requires careful analysis, according to MDPI.

Ultimately, the path to higher integration density may require rethinking fundamental circuit architectures. Rather than fighting thermal effects, future designs might embrace temperature variation, using adaptive calibration and thermal-aware signal processing to maintain performance across temperature ranges. Machine learning models can predict and compensate for thermal crosstalk with sub-picometer accuracy, suggesting that intelligent control systems might partially substitute for improved thermal isolation, according to arXiv.

The thermal management challenge in photonic integration is not merely an engineering obstacle but a fundamental physics constraint that shapes the technology’s trajectory. As the drive toward denser, faster, more efficient photonic systems continues, success will require not just better heat removal but smarter systems that minimize heat generation, intelligently distribute thermal loads, and maintain precise operation despite temperature variations. The thermal problem, long considered photonics’ elephant in the room, must be addressed head-on if the technology is to fulfill its transformative promise.