SRS Probes Inner Workings Of Solar Panels

Using femtosecond stimulated Raman spectroscopy (SRS), scientists have now probed the inner workings of plastic solar panels.

The findings could further efforts to improve solar panels and broaden their use, according to a team at the University of Montreal, in conjunction with England’s Science and Technology Facilities Council, Imperial College London and the University of Cyprus.

“Our findings are of key importance for a fundamental mechanistic understanding, with molecular detail, of all solar conversion systems,” said Françoise Provencher, a doctoral candidate at the University of Montreal.

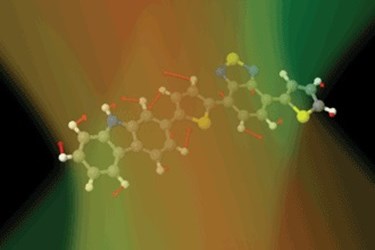

Specifically, the researchers have discovered how light excites the molecules and generates current in solar panels that are based on blends of polymeric semiconductors and fullerene derivatives.

“In these and other devices, the absorption of light fuels the formation of an electron and a (positively) charged species,” said lead researcher Dr. Sophia Hayes, an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Cyprus. “To ultimately provide electricity, these two attractive species must separate, and the electron must move away. If the electron is not able to move away fast enough, then the positive and negative charges simply recombine, and effectively nothing changes. The overall efficiency of solar devices compares how much recombines and how much separates.”

The researchers used femtosecond SRS to gather information on the vibrations of molecules. They found that after the electron moves away from the positive center, the molecules must rearrange themselves within around 300 fs. Such speed helps maintain charge separation, they said, noting that any ongoing relaxation and molecular reorganization processes following this initial charge separation should be extremely small.

“Our findings open avenues for future research into understanding the differences between material systems that actually produce efficient solar cells and systems that should be as efficient but in fact do not perform as well,” said Dr. Carlos Silva, an associate professor at the University of Montreal. “A greater understanding of what works and what doesn’t will obviously enable better solar panels to be designed in the future.”

The work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Research Chair in Organic Semiconductor Materials, the Royal Society, the Leverhulme Trust, Laserlab-Europe, the U.K. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the European Research Council and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

Source: The University of Montreal