MIPT Physicists Tune A Spin Diode

A team of physicists at MIPT has offered a new design of a spin diode, placing the device between two kinds of antiferromagnetic materials. By adjusting the orientation of their antiferromagnetic axes, it is possible to change the resistance and the resonant frequency of the diode. In addition, this approach triples the range of frequencies on which the device can rectify alternating current. At the same time, the sensitivity of the spin diode is comparable to that of its semiconductor analogs. The paper was published in Physical Review B.

“Conventional spin diodes with free ferromagnetic layers only operate on predetermined frequencies that don’t exceed 2-4 gigahertz,” explains senior researcher Konstantin Zvezdin of the Laboratory of Magnetic Heterostructure Physics and Spintronics for Energy-Efficient Information Technologies at MIPT.

“In this paper, we propose a diode with ferromagnetic layers pinned by antiferromagnetic layers. This enables the device to operate at almost 10 gigahertz, without sacrificing its sensitivity in any significant way. As a result, we expand the range of possible applications of spin diodes to include things like all-weather machine vision based on microwave holography, among others,” says the researcher who also leads a project focused on spintronics at the Russian Quantum Center.

Spin diode

Familiar electronic devices such as diodes, transistors, operational amplifiers, etc. manipulate electric currents. In other words, their operation relies on the flow of charged particles — electrons and holes. In a semiconductor diode, for example, there is a region called the p-n junction where a material with a large electron concentration meets the material with a large hole concentration. As a result, the electric current can only pass through the junction in one direction. Because of this, diodes can be used to build a rectifier — that is, a device that turns alternating current (AC) into direct current (DC).

The electron does not only carry a charge, though: It has another important property, spin, which is a quantum mechanical analog of a rotating body’s angular momentum in classical physics. Ordinarily, the spins of the electrons in an electric current are randomly oriented. However, it is possible to align them, resulting in a peculiar phenomenon referred to as spin current. Spintronics is the study of spin currents. By now, scientists have figured out how to manufacture spintronic nanogenerators, microwave radiation detectors, and magnetic field sensors that surpass their electronic analogs.

Like a semiconductor diode, its spintronic counterpart — the spin diode — works as a rectifier. It is made by inserting a layer of dielectric material between two thin ferromagnets. The operation of this device is based on the effects called tunnel magnetoresistance and spin-transfer torque. The basic idea is the following: As a current flows through the first ferromagnetic layer, the spins of the electrons align with its magnetization, resulting in a spin current. The electrons then tunnel through the dielectric material and run into the second ferromagnetic layer. Depending on the angle between this layer’s magnetization and the spins of the electrons, it may be easier or more difficult for them to pass through. Therefore, the resistance of the device is a function of the mutual orientation of the magnetic layers (first effect). At the same time, the electrons try to turn the second layer to make it easier for them to pass through (second effect). Therefore, when an AC flows through the diode, the magnetization of its layers — and with it the resistance — oscillates with the current, rectifying it.

This makes it possible to manufacture spin diodes with a sensitivity of over 100,000 volts per watt, whereas conventional Schottky diodes max out at 3,800. Sensitivity is defined as the ratio between the output DC voltage and the applied AC power. It is indicative of how well the device can rectify an electric current. One of the flaws of spin diodes is that their sensitivity is strongly dependent on the AC frequency, spiking near a certain resonance and rapidly fading to almost zero elsewhere. It should also be noted that the resonant frequencies of all previously manufactured spin diodes do not exceed 2 gigahertz. However, some applications, among them microwave holography, require diodes operating at higher frequencies.

Throw in a couple of antiferromagnets for good measure?

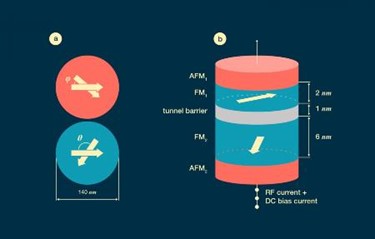

In their paper, the MIPT-based physicists describe a way to preset the diode’s resonant frequency during manufacturing and simultaneously increase its operating frequency. To achieve this, they stick the ferromagnetic “sandwich” structure between two antiferromagnetic layers. As a result, the ferromagnets become pinned to antiferromagnets in what is known as exchange pinning, allowing the angle between the magnetizations of the ferromagnets to be controlled. This enables the researchers to tune the resistance and the resonant frequency of the device. To test if the proposed design is feasible, the scientists numerically modeled a spin diode with layers that are several nanometers thick and studied its properties.

Here are the basics on ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic materials. In both of these, the spins of atoms exhibit long-range order — that is, the structure repeats itself. In a ferromagnet, the spins of all atoms are aligned in parallel with a certain axis, whereas in antiferromagnets they orient themselves perpendicular to the axis. To make this picture more realistic, you would also have to account for the effect of thermal fluctuations on spin orientations. Once a certain temperature is reached, spin orientations are completely randomized by the thermal fluctuations, ruining the long-range order and turning the material into a paramagnet. For ferromagnetic materials, this critical temperature is called the Curie point. For antiferromagnetic materials, it is known as the Néel temperature. Another feature of real-world materials is that the spins in them only exhibit alignment over macroscopic regions known as domains, not throughout the material.

What the model showed

First the team investigated how angle θ between ferromagnetic layer magnetizations depends on angle φ between the axes of the antiferromagnets. The latter, also known as the antiferromagnetic pinning angle, can be controlled during the manufacturing of the diode. It turned out that the angle between the magnetizations can only be varied between 110 and 170 degrees. Moreover, the dependence is nonlinear for the interval from 110 to 140 degrees. Nevertheless, this leeway is sufficient for controlling the properties of the diode.

The researchers went on to examine the dependence of diode sensitivity on AC frequency, fixing the angle between layer magnetizations. They found that near the resonant frequency, the sensitivity of the device increases sharply, reaching about 1,000 volts per watt. This value is lower than the maximum sensitivity of previously manufactured spin diodes, yet it is comparable to the same figure of merit of conventional semiconductor diodes.

Importantly, the resonant frequency of the new diode can be tuned in the range from 8.5 to 9.5 gigahertz by controlling angle φ when the device is manufactured. That said, the researchers have only studied their proposed design theoretically. The next step would be to create an experimental sample and use it to test their predictions.

In an earlier study, MIPT physicists excited magnetic vortices in spintronic devices based on a ferromagnetic material and a topological insulator. The latter is a peculiar material that acts as a conductor on the surface but is otherwise an insulator.

Source: MIPT