McGill Researcher Uses LiDAR To Reveal 600-Year-Old City In Mexican Jungle

By John Oncea, Editor

A groundbreaking LiDAR study has uncovered the full scale of Guiengola, a vast 15th-century Zapotec city in Oaxaca, Mexico, hidden beneath dense vegetation for centuries.

We’ve written about how LiDAR was instrumental in uncovering a 650-square-mile Maya site hidden in northern Guatemala and its role in revolutionizing research in Antarctica, including discovering several surprising features. Now, the remote sensing technology is at it again, helping reveal a vast, fortified, 600-year-old city in southern Oaxaca, Mexico.

Led by archaeologist Pedro Guillermo Ramón Celis, a Banting postdoctoral researcher in McGill’s Department of Anthropology, “The research found that Guiengola, or ‘Large Stone’ in Zapotec, was much more than a military outpost: The site possesses temples, ball courts, distinct residential zones for elites and commoners, and a complex system of roads and strongholds,” writes Archaeology Magazine.

“You can walk there in the jungle and find that houses are still standing – you can see the doors, the hallways, and the fences that separate them from other houses,” said Ramón Celis in a statement. “It’s like a city frozen in time before any of the deep cultural transformations brought by the Spanish arrival had taken place.”

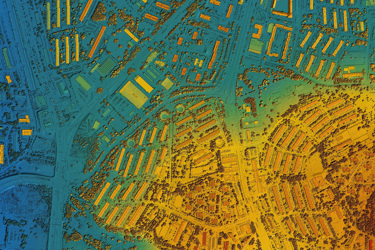

Thanks to LiDAR technology, archaeologists mapped the entire site in just two hours – something that otherwise would have taken years on foot. This advanced remote sensing technique allowed researchers to penetrate the dense forest canopy that had long concealed the site’s full extent.

More Than A Military Outpost

Guiengola is a significant archaeological site of the Zapotec civilization, located approximately 9 miles north of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, Mexico. “The site of Guiengola is an example of one of the settlements built by the Zapotecs during their fourteenth- to fifteenth-century migration to the Southern Isthmus of Tehuantepec,” writes Ramón Celis. “Although Guiengola is well known in the ethnohistorical record as being the place where the Mexica armies were defeated by Zapotec … the full extension of the site was previously unknown.”

Guiengola played a key role in the Zapotec resistance against Aztec expansion, with a decisive battle fought there between 1497 and 1502, writes The Art Newspaper. The Aztecs, under the leadership of Ahuízotl, laid siege to Guiengola for seven months but ultimately faced a rare defeat, an event that underscored the strategic importance and defensive capabilities of the city. However, by 1521, following the Spanish conquest, the Zapotecs were forced into submission, leading to the destruction of their cities and the assimilation of their culture.

This discovery sheds new light on the incredible urban planning and resilience of the Zapotec civilization. The architectural features of Guiengola are emblematic of Zapotec engineering and urban planning. Central to the site are two plazas at different elevations, flanked by eastern and western pyramids. Excavations have uncovered two primary tombs believed to be family burial sites, each comprising front chambers for religious idols and rear chambers for interring prominent individuals.

“The findings of this project expand our understanding of the variations and social divisions in the city’s internal urban organization, which in turn, allow us to deepen our comprehension of the transition to the Early Colonial barrio organization of Tehuantepec,” Ramón Celis writes.

The recent revelations about Guiengola have significantly enhanced our understanding of the Zapotec civilization’s social and political complexities during the Postclassic period. The site’s extensive urban infrastructure and formidable defenses reflect a society with advanced organizational skills and a rich cultural heritage. Ongoing archaeological efforts continue to shed light on the daily lives, traditions, and resilience of the Zapotec people who once thrived in this remarkable city.

LiDAR’s Role In Finding Guiengola

“Constructed during the 15th century, Guiengola is located on a plateau covered in a thick forest canopy, which has hindered previous attempts to map the site,” The Art Newspaper writes. “From oral history and Spanish sources, however, the location is known as the fortress where the Zapotecs – a civilization from the nearby Central Valleys of Oaxaca, who flourished from roughly 700BCE to 1521CE – defended themselves from an Aztec invasion, an event that included a seven-month siege and culminated in a rare Aztec defeat.”

“My mother’s family is from the region of Tehuantepec which is about 12 miles from the site, and I remember them talking about it when I was a child. It was one of the reasons that I chose to go into archaeology,” Ramón Celis said. “Although you could reach the site using a footpath, it was covered by a canopy of trees.”

Until recently, there would have been no way for anyone to discover the full extent of the site without spending years on the ground walking and searching. LiDAR, a remote sensing technology that relies on pulsing laser beams, in a process akin to sonar, to provide precise, detailed, three-dimensional topographic information about what is on the earth’s surface, below the dense forest canopy, changed everything.

By analyzing the data generated by the scans and using the Geographic Information Centre’s resources at McGill, Ramón Celis has been able to map the size and the layouts of the remaining built structures and infer their use based on the artifacts found at the locations.

To explore how power was distributed in the city, he calculated how much building space was given over to elite areas such as the temples and ballcourts, for example, compared to what was built in the areas used by commoners, Phys.org explains. Ballcourts were built in Mesoamerica to practice a ritual ballgame and represent both the underworld and fertility since they are a way of connecting with the ancestors and seeds grow below the soil, where the underworld is found.

A Place Of Pride

The success of LiDAR in this context underscores its value in archaeology, particularly for sites concealed by dense vegetation. Traditional ground surveys would have been time-consuming and potentially disruptive to the site. In contrast, LiDAR offered a non-invasive means to obtain high-resolution data over large areas efficiently.

The revelations at Guiengola not only enhanced our understanding of Zapotec urban planning and architecture but also demonstrated how modern technology can reshape interpretations of historical sites.

Ramón Celis, when asked about the discovery, said, “It was certainly exciting; Guiengola is a place of pride for the descendant Zapotec people, as it is where they defeated the Aztec invaders. My future research will focus on understanding how this conflict occurred and the military technologies that existed in Mesoamerica, including how these walls were designed and the different tactics the Aztecs could have deployed in their attempt to conquer this land.”