Laser-based Mammography Unit Performs Both Absorption and Fluorescence Imaging

By: Laurie Ann Toupin

Integrating a single solid-state laser with a double-row detector array, engineers at <%=company%> (Fort Lauderdale, FL) have developed an optical mammography system that will potentially be able to treat breast cancer in the future.

The Computer Tomography Laser Mammography (CTLM) breast-imaging system maps local changes in the optical scattering and absorption coefficients over cross sections of the breast. Although the design is not quite ready for prime time, two clinical studies are currently under way at the University of Virginia and Nassau County medical centers.

The system has been under development for the past five years, but the designers have made perhaps the biggest improvements in the system within the last six months&151;after the CTLM's first "live" performance in a hospital setting.

Thermal instability

In the CTLM, the patient lies prone on a table with a breast dangling down through an aperture in the bed, called the scanning chamber. Nothing and no one physically touches her. The laser light, emitted on a horizontal plane perpendicular to breast, rotates 360°. A technician acquires data at one level, then moves the detector and laser downward approximately 4 mm to image another section.

The original design incorporated two neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) lasers, one mode-locked titanium-doped sapphire (Ti:sapphire) laser, and one Ti:sapphire regenerative amplifier (RGA).

"After our first clinical test, we quickly saw that the real world environment of the hospital was quite hostile compared to our lab," says IDSI CEO Richard Grable, noting that temperatures can quickly swing 5 to 10º, creating instabilities in the beam. "[Thermal variation] greatly influences how these lasers operate," he continues, "particularly the RGA and the Ti:sapphire, which generate a great deal of their own ambient heat. This caused us a significant headache."

Robust and compact

To minimize thermal dependency, the group took an entirely different tack, designing a fiber-coupled diode laser with a proprietary controller for temperature and power. The new laser operates in the 750 to 800 nm wavelength range, with an output of 500 mW. The wavelength chosen varies depending on whether the application is fluorescence imaging or regular imaging.

"The high-powered diode-pumped lasers with 8 and 10 W green light [on the market today] didn't have the life expectancy we needed," Grable says. "Plus we were throwing away 99% of the power. We expect our new laser to last longer that I expect to live."

In addition to the decreased size and decreased cost of lasers, came increased reliability. "Reliability is a big thing in hospitals," Grable notes. "Downtime doesn't help patients. The way the lasers were before, we didn't have the uptime we needed to get the throughput." This isn't an issue with the new system.

Another drawback to the earlier design was the use of fiber optic cables to transmit the captured light to the detector electronics. "We found we were getting an efficiency of 60% and throwing away 40% of our light. This is fine if you are working with a powerful output, but we were losing part of the signal we were trying to detect," says Grable. The group solved the problem by positioning the large area photo diodes closer to the breast and reducing the number of fiber optic cables to one.

Between the single laser and this detection design that eliminated the need for many of the special optical amplifiers initially used, the whole system shrank to 45% of its original size, says Grable. "All we have now is a single console with the computer, a 21" monitor, keyboard, and the scanning bed where the patient lies down." (see Figure 1, at top).

Acquiring the image

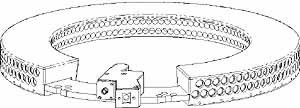

In addition to identifying potential lesions through changes in absorption of breast tissue, the scanner also performs florescence imaging. To acquire absorption and fluorescence data at the same time, he engineering team developed a two-row detector array . "We had been looking at how to acquire two slices of data simultaneously," says Grable. Designers decided to use two detector arrays arranged on the circumference of a circle, with the detecting surfaces facing in toward the center (see Figure 2), The top row maps the inner structure of the breast by imaging the light diffused the body. The bottom row images a fluoresced signal.

Researchers at IDSI experimented with indocyanine green (ICG), a pharmaceutical with an absorption wavelength in plasma of about 805 nm and a florescence of 836 nm. An optical filter inserted in front of the detectors on the second row blinds them to wavelengths shorter than the florescence wavelength of ICG. The resultant image indicates tumors by showing areas of increased absorption of ICG as well as increased florescence.

When the absorption and florescence images are overlaid, a diagnostician can determine the exact location of the problem. "And because both of these images are done at the same time with the same detector arrangement, they are already co-registered and aligned," says Grable. "To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time this type of imaging has been done anywhere in the world."

Diagnostics, therapeutics

Because the scanner images fluoresce, a surgeon can use a biochemical florescence tag to locate the tumor and then turn around and use the same device to treat the disease through photodynamic therapy. In photodynamic therapy, specially-developed photoresponsive drugs preferentially locate in cancerous tissue. When the compounds are illuminated by light at the activating wavelength, they release free radical oxygen that immediately kills the adjacent cells.

Currently, photodynamic drugs have been approved for prostate, skin, throat, and lung cancer. "We're betting that a pharmaceutical company will develop one that is useful for breast cancer therapy and then our scanner will be able to help treat as well as detect," says Grable.

"We hope to have some version of our scanner marketable by Thanksgiving," says Grable. "A year ago, I had some reservations about its marketability because we needed the laser to act like a light bulb—to repeatedly turn on and off and last for a while. But we've overcome all those hurdles. It's been an exciting last six months."