Startup To Acquisition: Industry Experts Weigh In

By Ed Biller, Editor, Photonics Online

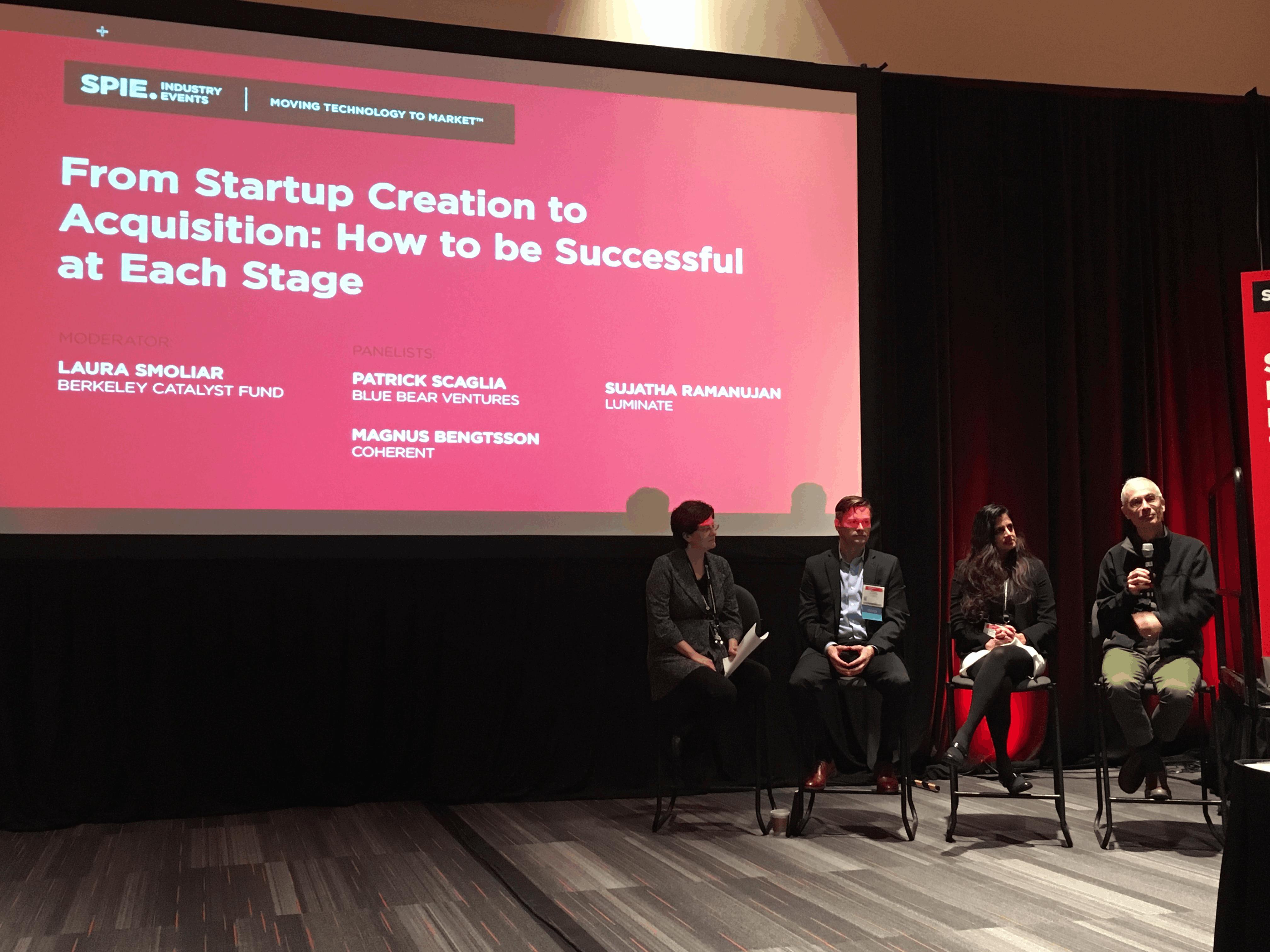

One of the highlights at Photonics West this year was a panel discussion featuring experts from all points along the path from establishing your technology to formulating an exit strategy.

Titled From Startup to Acquisition: How to Be Successful at Each Stage, the event’s panelists included Blue Bear Ventures’ Managing General Partner, Patrick Scaglia; Luminate Managing Director Sujatha Ramanujan; and Coherent VP of Strategic Marketing Magnus Bengtsson.

One of the first questions startups face — once their technology works demonstrably — is whether to sign on with an incubator or an accelerator, if either.

“The most distinct difference between accelerators and incubators is the time frame of each. An accelerator works with startups for a short and specific amount of time, usually from 90 days to four months. Accelerators also offer startups a specific amount of capital,” writes Bill Clark of MicroVentures. “With mentorship periods often lasting more than a year and a half, incubators focus less on quick growth and have no specific goal in mind for your company other than to become successful at the right pace.”

Further, competition can be fierce to partner with such entities. Scaglia’s Blue Bear is a venture capital (VC) fund affiliated with CITRIS Foundry, a startup accelerator embedded in UC Berkeley.

“[Startup success is] happening, but it’s happening through sheer strength of will of the founders, and not because somebody is helping them,” he said, adding that accelerators like CITRIS Foundry help startups get “to a point where they have enough for a VC firm to [invest] money into.”

In this case, “enough” equals a viable business plan and an identifiable initial customer.

Scaglia said CITRIS looks at three determining factors:

- First, the startup should offer more than just a technology; its tech should have the potential to be a product. “It’s time to go to an investor once you have a customer,” he said, noting that a customer could send a letter of intent to your potential investor, showing they are committed to your product.

- Second, what is the team dynamic like? The team may be all researchers, so who handles the business end? How do you split ownership? This latter question is one of the toughest early decisions a company will have to make.

- Third, what is the team’s coachability? “Can you learn by being guided?” Scaglia asked the audience. “For me, this is the most important [factor].”

Ramanujan’s Luminate is an industry-specific accelerator focused on optics, photonics, and imaging startups. She explained that incubators are a better option for less mature startups.

“A good incubator should help decide if you really have a business, and what it will take to grow,” Ramanujan said. “It’s like boot camp for when you start a business. As such, you have to look at, ‘who are the mentors?’”

The answer to this question is vital, since incubators’ and accelerators’ experience will help startups to avoid costly mistakes.

“Do your homework; no two accelerators are the same,” Scaglia said, adding “it’s like fundraising for your venture: you are going to get a lot of rejection.”

Other factors for startup founders to consider include business location and alternative/additional investment resources. For example, there exist lots of incentives for woman-owned and minority-owned businesses, Ramanujan pointed out. Manufacturing assistance and energy-related grants are there for the taking, as well.

“The help is out there, but you have to ask for it,” she said. “And, depending on where you are, if job/industry growth in a particular sector is on the radar of legislators, there may be money available. You might reconsider locating your business to an area that has these types of programs, if you’re struggling [where you’re at].”

Both Ramanujan and Scaglia said that location has a huge effect on talent pool, as well.

“Make sure you locate in a place where, the people you want to hire, they want to live,” Scaglia said. “Those first three, four, five, or ten hires are going to make or break your business.”

Further supporting the careful-where-you-put-down-roots argument was Coherent’s Bengtsson.

“Most of our locations around the world [and there are more than a few] are the result of acquisitions,” he said.

Exit Strategy and Wooing Acquirers

Some founders think they can accomplish anything themselves, Scaglia said, and startup leaders must be honest with themselves about their strengths and weaknesses before that question can be answered.

“To be successful as a startup, you have to want to bring the startup to something big. You have to discover what you really WANT to do. There is a long path between a dream and actually entering the market,” he said, advising founders to ask themselves, “Where do we see this business going, and can WE take it where we want it to go? It’s all about momentum. What can you do to get momentum to the next step?”

Additionally, as panel moderator Laura Smoliar —Founding Partner and Managing Director of the Berkeley Catalyst Fund — pointed out, “we don’t often have visibility on what an acquirer thinks, and what they’re looking for.”

Bengtsson said acquirers look at what they have, what they need, and what is required to get them where they want to be. Scaglia added that, sometimes, acquisitions are made in the name of risk management.

“You can acquire to get additional technologies, new components, or to grow vertically [allowing you to produce that tech or tap that expertise in-house],” Bengtsson said.

He said that startups facing acquisition “will get a lot of questions you were not expecting. Be prepared for the diligence [of acquirers], especially with a public company that doesn’t want a lawsuit or a PR disaster.”

Acquisition preparation includes establishing a reliable supply chain, the quality/reliability of your product, and common-sense customer and investor contracts. This last item can be the trickiest.

Bad decisions can happen because your startup needs money, Bengtsson said, but bad contracts can sink an acquisition.

“Read the contract and try to push back. This WILL affect the valuation of the company,” he said.

Scaglia also shared a horror story of an acquisition that was scuttled due to a startup’s existing contracts with customers being so bad, while Ramanujan cautioned startup leaders to “think hard about taking [investments] below $300,000” — consider where that money is coming from, as well as the entity’s motivations.

Regarding supply chain, Bengtsson said Coherent looks more “for processes: do you actually know what you’re doing, or did you do something and it just happened to work once?”

The corporate investment map is fairly straightforward, added Ramanujan: money required + time to market + IP position.

“The supply chain [that goes] into making your product is one thing; supply chain into volume manufacturing is completely another,” she said.

Ramanujan continued that knowledgeable tech leaders and supply chain managers for the company you’re interested in are your key targets when seeking acquisition. If the supply chain manager doesn’t believe in you, your business isn’t going anywhere.

As far as product quality and reliability, Ramanujan made it clear that acquirers aren’t pinching pennies: quality trumps cost. While acquirers understand the difficulty in establishing that long-term reliability for a startup, Bengtsson added, “The further it is along that path, the better.”

Still, for all the difficulty and inevitable disappointment inherent in being part of a startup, the reward for founders achieving their goals is one worth chasing.

“Just because it doesn’t happen now, doesn’t mean it won’t happen later,” Bengtsson said.